Historic Quaker Houses of Philadelphia

Stenton

Built 1730 by James Logan

Secretary to William Penn

Above: Stenton, a house museum and National Historic Landmark in Germantown. Image source: Lee J. Stoltzfus

Stenton is one of the earliest and best-preserved houses of colonial Philadelphia. It was the home of Quaker politician and merchant James Logan and wife Sarah (Read) Logan. The house is an outstanding example of early Georgian architecture.

The house exterior is plain, “suggesting that in Quaker Philadelphia affluence was no sin—only its superfluous expression.” Quote: George E. Thomas, SAH Archipedia.

Irish Quaker Immigrant James Logan

One of the Most Prominent Men of Colonial Pennsylvania:

Above: Portrait of James Logan (posthumous) by Thomas Sully, painted in 1831. Image Source: Library Company of Philadelphia

James Logan acquired great wealth as a fur trader and transatlantic merchant. He held many of the highest political and judicial offices of the Pennsylvania including:

1. Secretary and chief administrator to William Penn

2. President of the Provincial Council

3. Mayor of Philadelphia

4. Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court

5. Acting Governor of Pennsylvania

Image source: Great American Treasures

Above: Stenton’s yellow lodging room is restored and furnished to reflect its appearance circa 1750. The woodwork is painted with a vibrant yellow ocher paint.

The Logan High Chest and Dressing Table

In their Original Yellow Lodging Room at Stenton:

Image source: Cstorb.com, Christopher Storb.

Above: The ca. 1738 high chest and dressing table are included in Logan’s 1752 inventory. They are listed as “Maple Chest of Drawers & Table”. The inventory lists these case pieces in the yellow lodging room where they stand today. Cutouts in the room’s woodwork reveal the original location of the high chest, where it continues to stand on display.

Georgian Architecture Pattern Books

in Colonial Philadelphia:

Above: Drawings of Daniel Campbell’s Shawfield Mansion in Glasgow, Scotland, published in Vitruvius Britannicus, or the British Architect, by Colen Campbell, 1722, Vol 2. Image source: Internet Archive.

Architecture pattern books such as Vitruvius Britannicus (1715 - 1725) introduced Georgian architecture to 18th-century Philadelphia. The city and surrounding area showcase many Georgian buildings whose designs were shaped by these influential British publication.

The front elevation of Logan’s Stenton is like a plain Quaker version of Daniel Campell’s Shawfield Mansion in Glasgow. Logan chose simple brick pilasters to add vertical elements to his house facade, while Daniel Campbell chose ornate stone quoins for his vertical accents.

Stenton originally had a balustraded gallery at the peak of the roof, similar to the Campell house. James Logan named his Philadelphia estate “Stenton” after the village in East Lothian, Scotland, where his father was born.

An Irish Counterpart to Stenton

The 1667 Waringstown House in Northern Ireland:

Above: Image sources: Book cover: Amazon.com. Book text: An Introduction to Ulster Architecture Internet Archive. Waringstown House: LordBelmont. Stenton: Lee J. Stoltzfus.

James Logan was born in Lurgan, County Armagh, Ireland, in 1674 to a Quaker family of Scottish descent. His father, Patrick Logan, was a schoolmaster and former Church of Scotland minister who converted to Quakerism. The Logans had left Scotland for Ireland seeking religious tolerance.

Logan stayed connected to the Society of Friends throughout his life, but his actions sometimes conflicted with Quaker values. He supported military defense during colonial conflicts, which clashed with Quaker pacifism. His land deals sometimes conflicted with Friends’ ideals. These tensions strained his standing with more conservative Quakers, but he never formally left the faith.

Quaker Architecture is “Ostentatiously Humble”

Above: “Quaker architecture is deliberately lowkey, ostentatiously humble.” Quote: Dr. Michael J. Lewis, Williams College, PhilaAthenaeum. Image source: Lee J. Stoltzfus

The facades of Pennsylvania’s early Quaker houses often seem humble in their simplicity. The public faces of these homes are mostly unadorned, with no excess ornament. These exteriors feel elegantly restrained.

Meanwhile, the large-scale proportions of these historic Quaker plantation houses place these homes in an elite league of their own. The lavish craftsmanship of the interiors spared few expenses. The interior workmanship is of the finest sort, and the beautiful rooms sometimes feel sinfully sumptuous. But compared to English pattern books, the facades of these attractive Quaker houses are Pennsylvania plain.

Hope Lodge’s front facade originally was ever more minimalist than it is today. Later additions to this house include the dormers, the entry hood, and probably the exterior shutters.

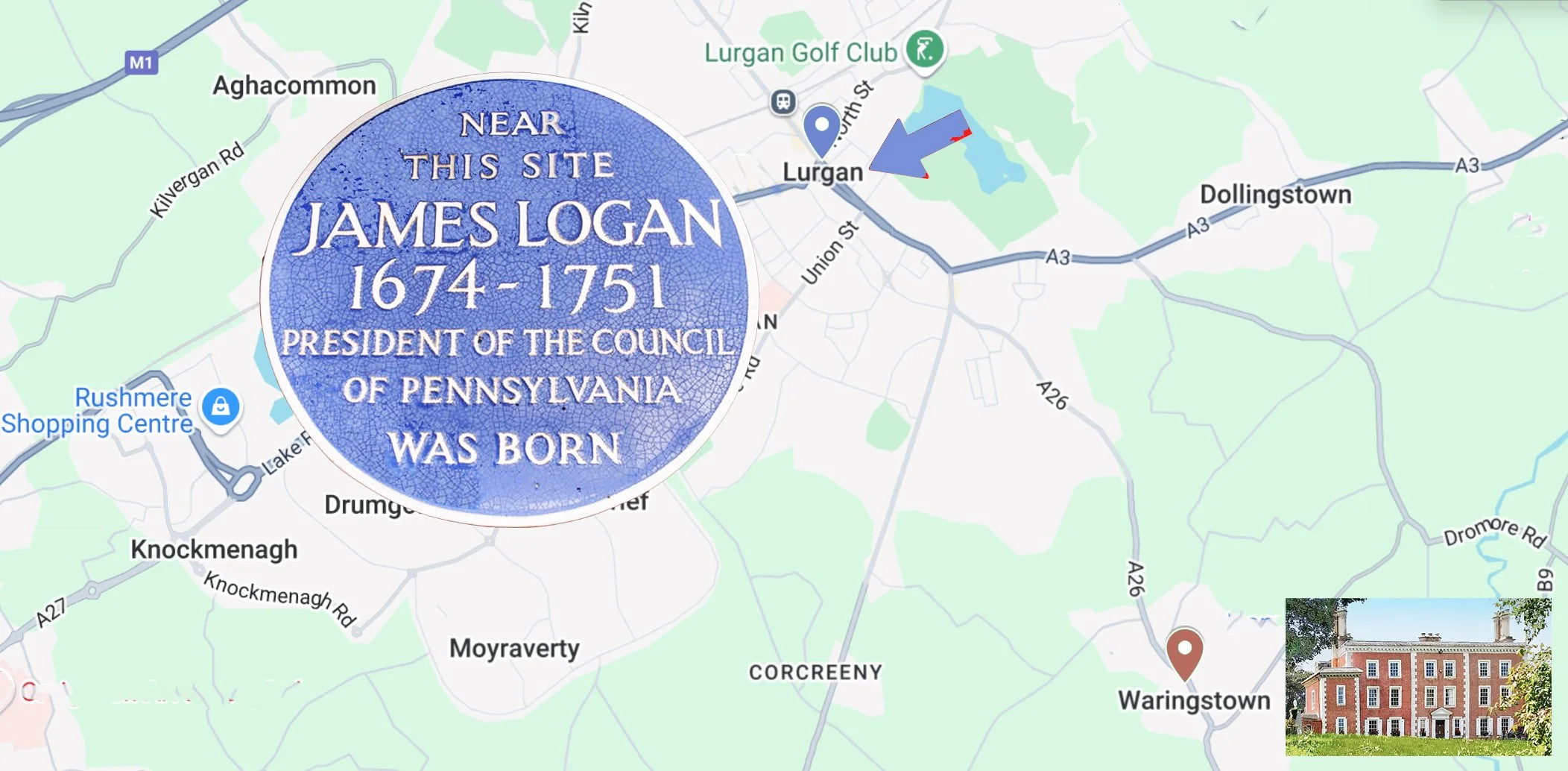

Historical Marker for James Logan’s Birthplace

in Lurgan, Northern Ireland

With a Stenton Architectural Counterpart Nearby: Waringstown House:

Above: Image sources: Google Maps. Historical Marker: Wikipedia. Waringstown House: LordBelmont

Stenton’s distinctive facade (ca. 1730) shares features with the 1667 Waringstown House, located less than 4.8 kilometers (three miles) from Logan’s hometown of Lurgen, Northern Ireland. Similar details include six bays of windows flanked by pilasters (Stenton) or quoins (Waringstown House), and a central entry flanked by narrow sidelights which are flanked by pilasters. Stenton originally had a hood or similar protection over the entry, a counterpart to Waringstown House’s entry pediment.

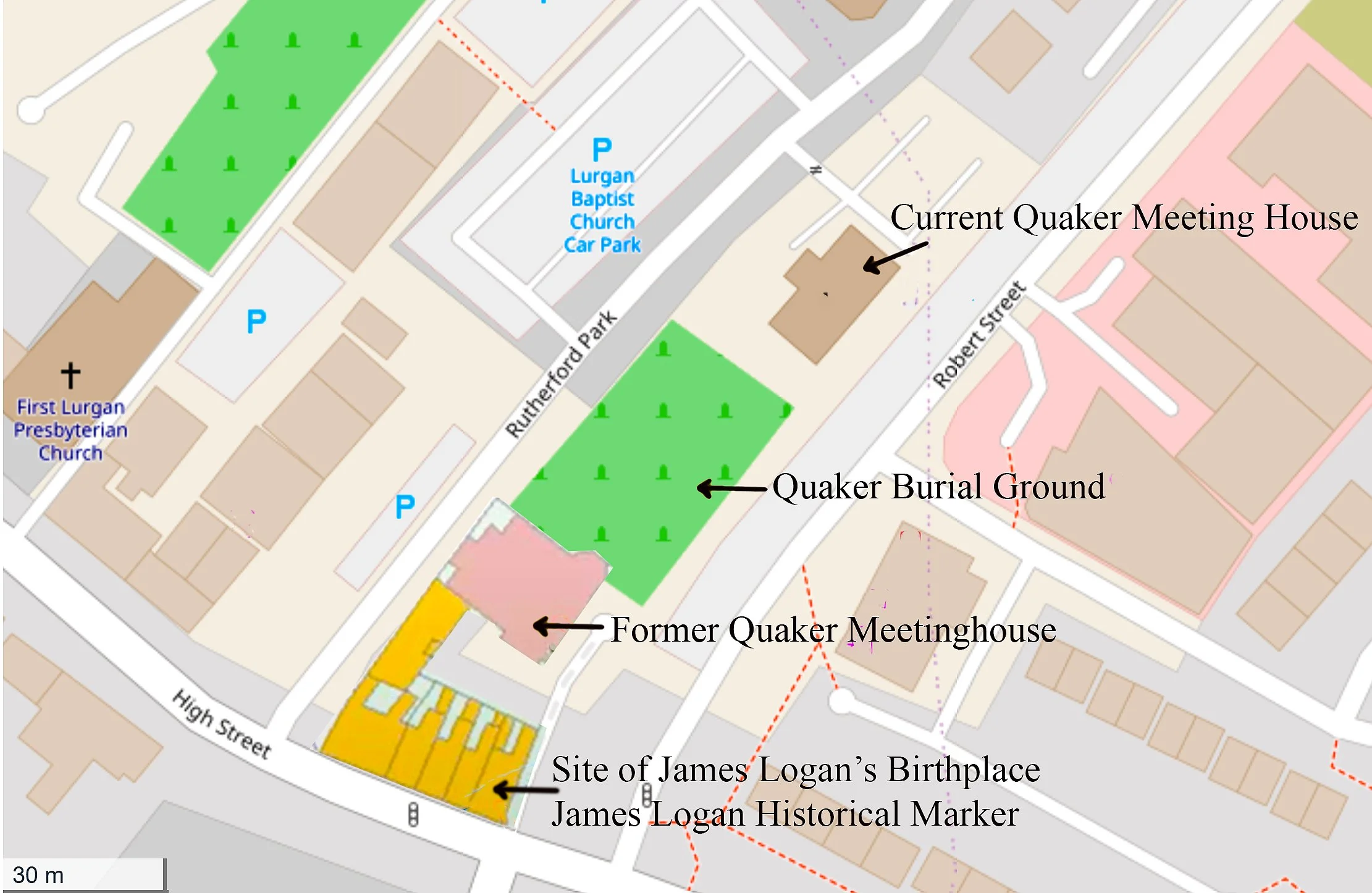

Map of Quaker Meeting Houses in Lurgan, Northern Ireland

Birthplace of James Logan:

Above: Image source: OpenStreetMap, with additions.

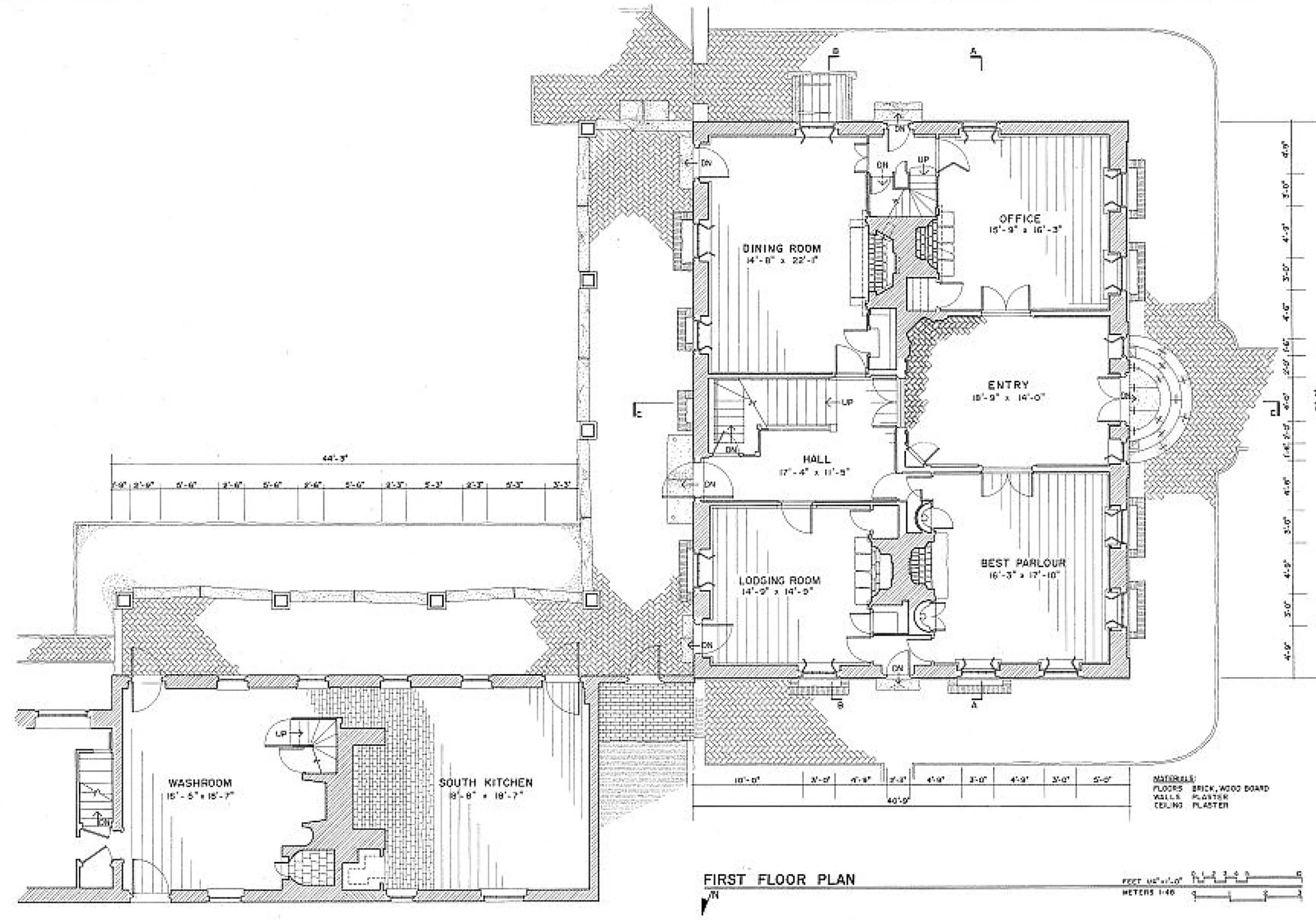

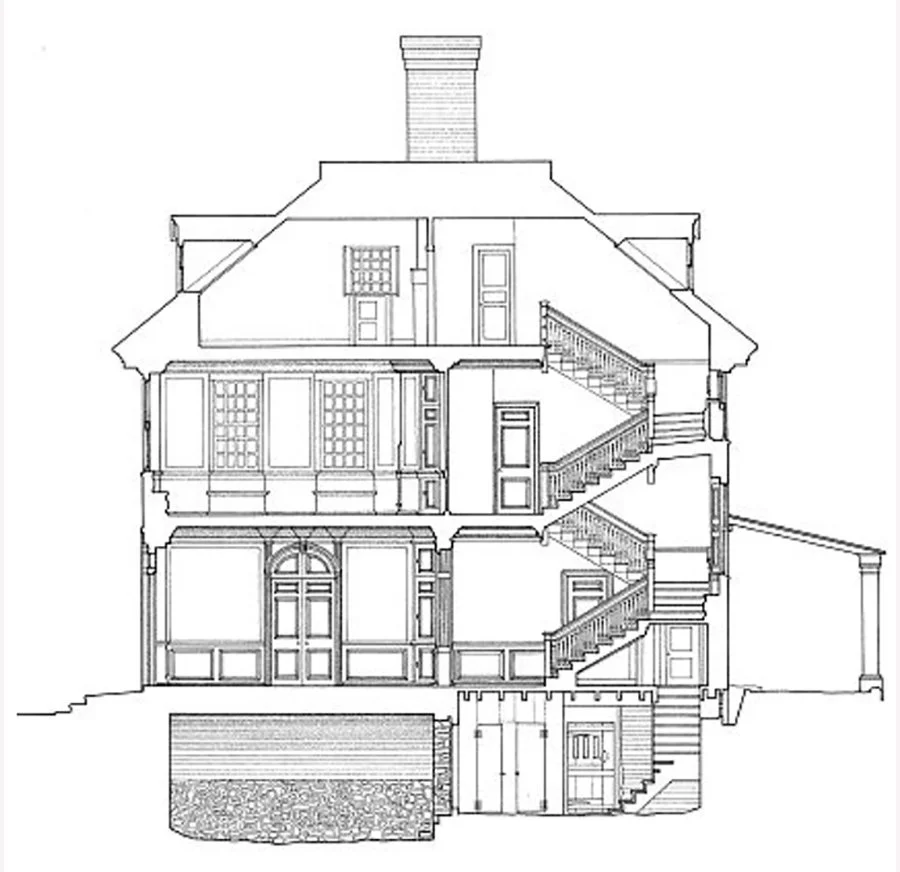

Stenton Floorplan and Sections

Historic American Buildings Survey:

Above: Stenton floorplan, drawn by Rebecca Trumbull Wiesenthal and Mary Ellen Strain, 1998. Image source: Historic American Buildings Survey

Above: Stenton section, detail, drawn by Rebecca Trumbull Wiesenthal and Mary Ellen Strain, 1998. Image source: Historic American Buildings Survey

Above: Stenton section, detail, drawn by Rebecca Trumbull Wiesenthal and Mary Ellen Strain, 1998. Image source: Historic American Buildings Survey

James Logan, Renaissance Man:

Scientist, Scholar, Botanist, and Patron of Learning:

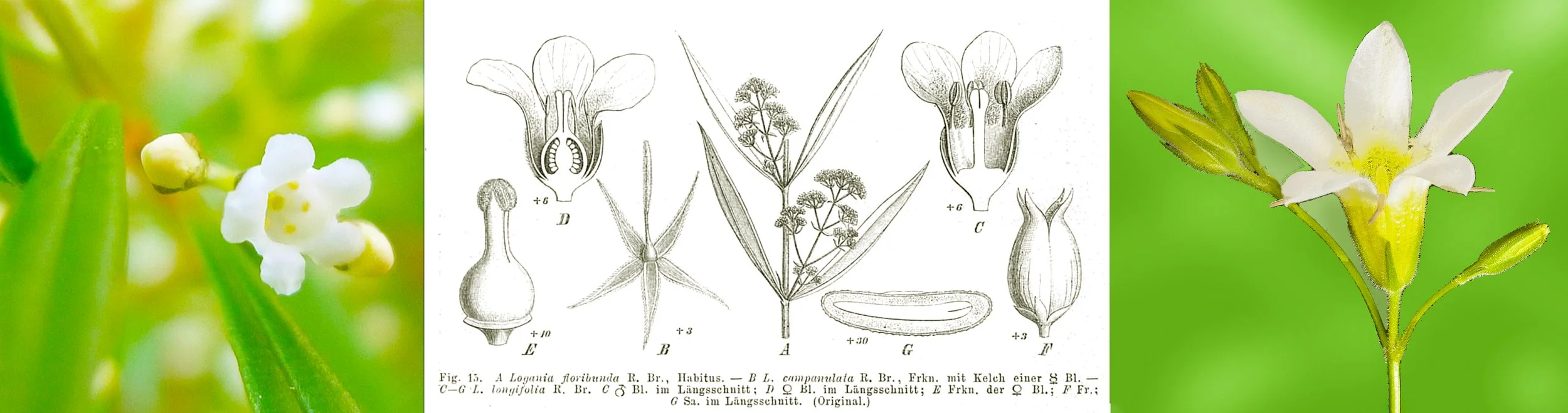

Above left Logania albiflora, Above center: Botanical illustration of three Logania species in Die natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien, Engler, 1892, Above right: Logania campanulata. Image source: Wikimedia: John Tann and Kevin Thiele.

In 1810, the Scottish botanist Robert Brown named the plant genus Logania in honor of James Logan. Brown, widely regarded as one of the most influential naturalists of the 19th century, included the new genus in his groundbreaking botanical work Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae, which documented the flora of Australia. Although Logan never visited Australia, Brown recognized Logan’s early experiments on plant reproduction, especially his work on maize as significant contributions to botany.

James Logan

One of the Most Learned Men in Colonial Pennsylvania:

1. Linguist, Scholar, and Bibliophile

Logan was fluent in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and deeply read in philosophy, mathematics, botany, and astronomy. His personal library was the largest in the colonies.

2. Member of the Royal Society

This was a major recognition of his scientific reputation in England and abroad.

3. Correspondent of Leading Scientists

Logan corresponded with Isaac Newton, Carl Linnaeus, and other top thinkers. He shared botanical observations and discussed scientific theory, especially in mathematics and physics.

4. Discoveries in Plant Biology

Logan conducted experiments on plant reproduction. In 1739, he published a paper on the fertilization of maize concluding that pollen was necessary for seed production. Linnaeus cited this work approvingly.

5. Translator and Publisher of Classical Texts

He translated and published Cicero’s Cato Major in 1744. This is the first classical work printed in America in its original Latin.

James Logan’s Private Library

The Best Book Collection in Colonial America

Donated by Logan to the City of Philadelphia:

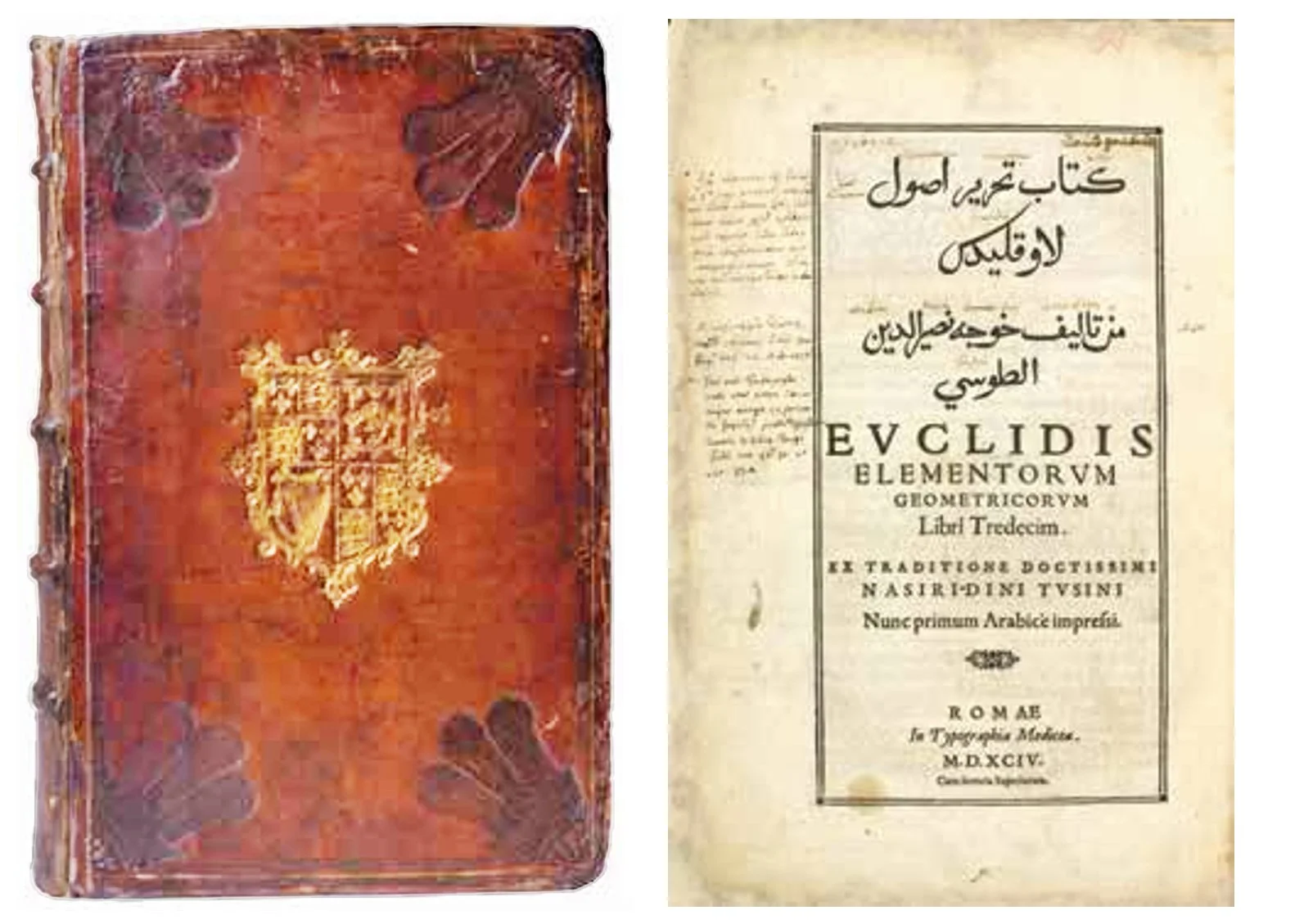

Logan’s books: Above left: Geoffrey Chaucer, Works. London, 1602, originally bound for Henry, Prince of Wales, with his arms and feather insignia. Right: Euclid in Arabic. Rome, 1594, with marginal notes in Arabic by James Logan. Image source: Library Company

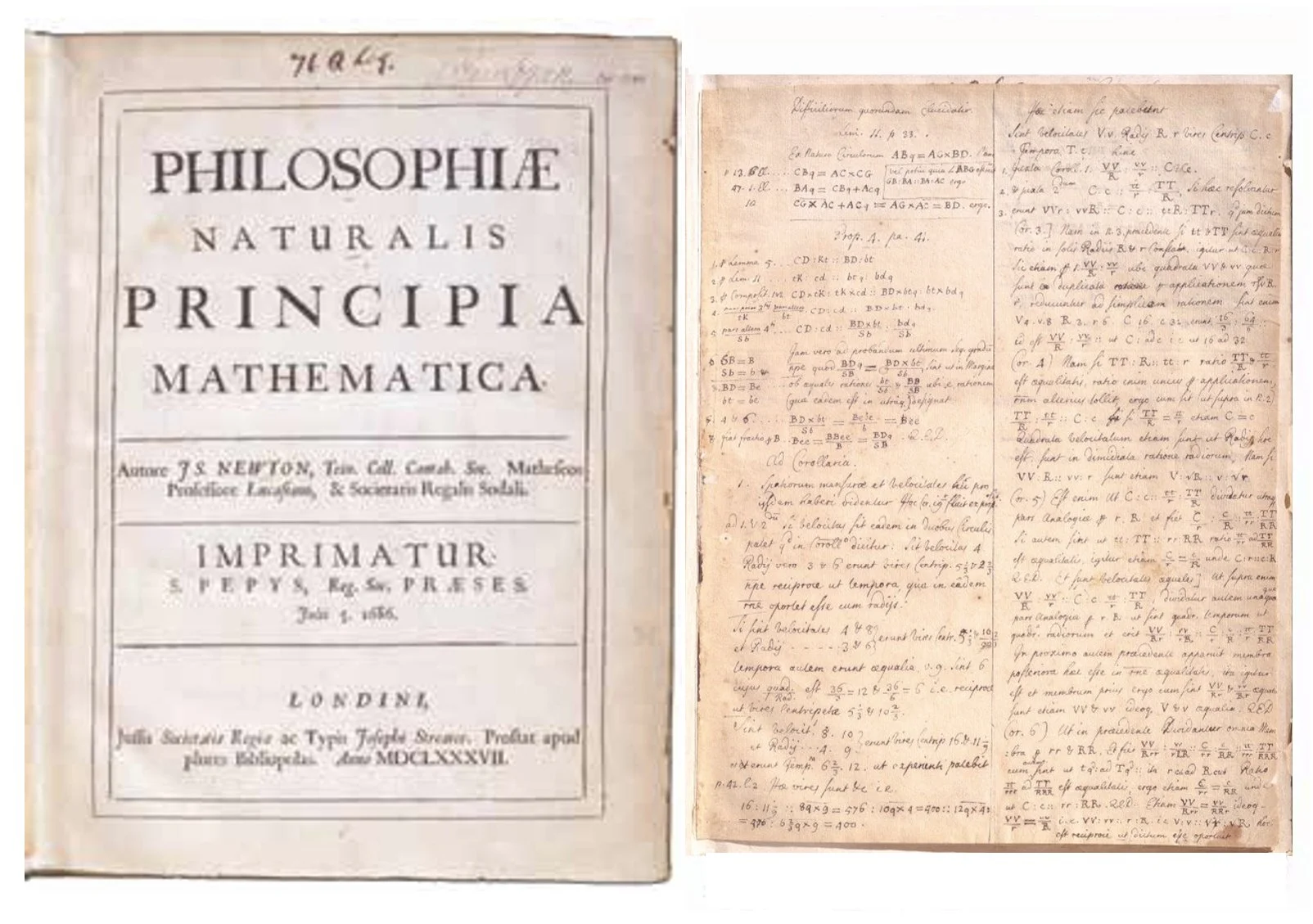

Logan’s books: Above left: Isaac Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. London, 1687. Right: Difficiliorum quorundam Elucidatio: Manuscript explanations by James Logan of Newton’s principles, tipped into the front of the Principia. Image source: Library Company

“ …Logan had gathered over 2,600 volumes, chiefly in Latin and Greek, constituting the best collection of books in colonial America.” Quote: “At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin,” The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2015.

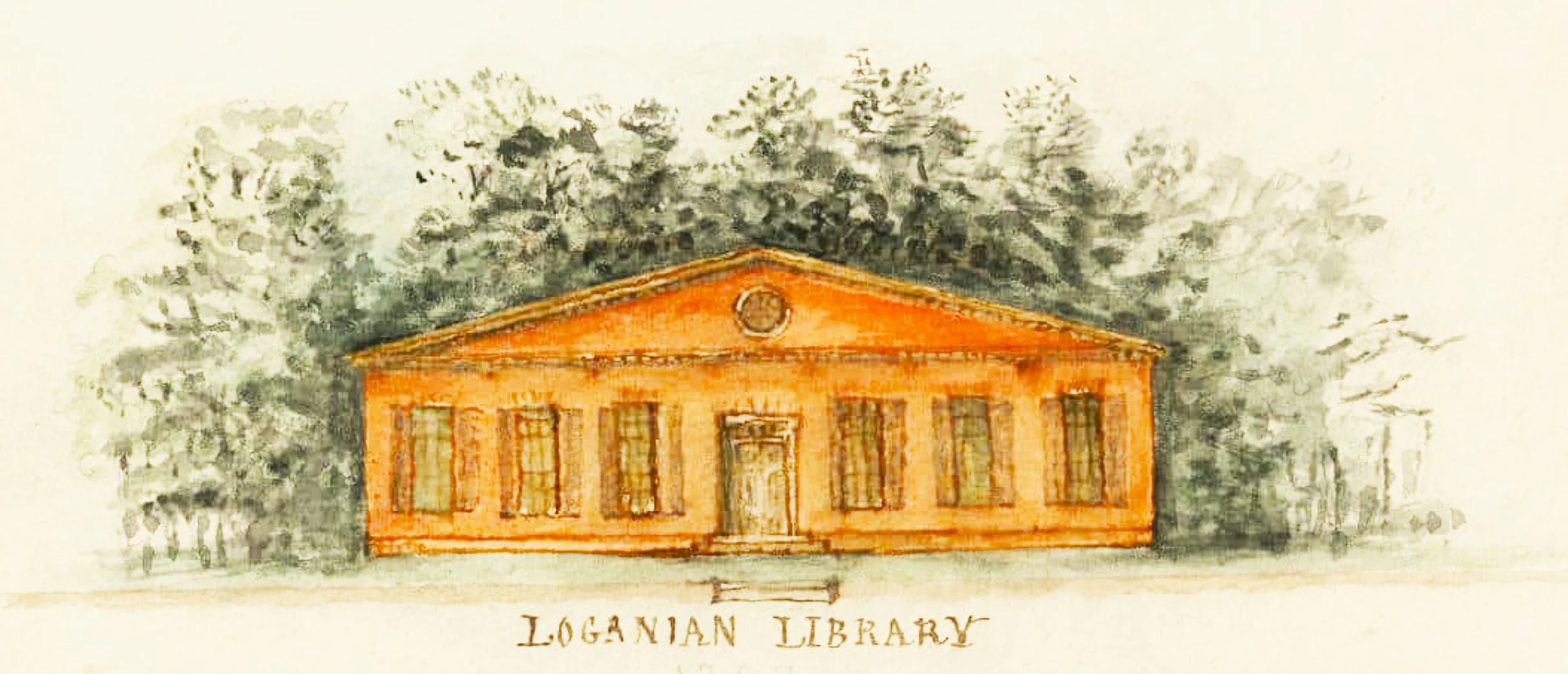

James Logan left his books for the use of the public, following by the example of Oxford University’s Bodleian Library. He designed a building on Sixth Street, Philadelphia, to house the library, and endowed the institution in his will. The Loganian Library was created in 1754 as a trust for the public. Ben Franklin was one of the trustees. In 1792 the library was transferred to the Library Company, where it remains today.

The Loganian Library

Above: A ca. 1797 ink-and-wash drawing of the Loganian Library, founded by James Logan with his book collection. Image source: Library Company of Pennsylvania.

James Logan’s Loganian Library was widely considered one of the finest, if not the finest, private libraries in colonial America. His collection of scientific and mathematical books even surpassed Harvard College's library in 1735. Logan’s library focused heavily on classical literature, philosophy, science, mathematics, and theology, with texts in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, and several modern European languages.

What made the Loganian Library stand out wasn’t just its size but its scholarly depth. Logan was a serious intellectual and scientist, and he collected rare and important works. Many of his books were unavailable elsewhere in the colonies. His library reflected European Enlightenment thinking and was regularly consulted by other leading colonial thinkers, including Benjamin Franklin.

The Stone Bank Barn at Stenton

Built in 1787 by Dr. George Logan:

Above: The Stenton bank barn. Ventilation slits puncture the stone walls. Image source Lee J. Stoltzfus

Above: Dr. George Logan, a grandson of James Logan, built this barn in 1787. Dr. Logan was a physician, farmer, and politician. He lived here at Stenton with wife Deborah (Norris) Logan. Thomas Jefferson described George Logan as “the best farmer in Pennsylvania, both in theory and practice.” Dr. Logan was a founder of the Pennsylvania Society for the Promotion of Agriculture.

Dr. Logan served in the Pennsylvania legislature and in the U. S. Senate. In 1791, the Quakers disowned him because he joined a militia, which opposed the Quaker peace testimony. Although Dr. Logan became officially separated from the Quakers, he never completely turned his back on Friends’ traditions. He never joined another religious group, and later in life he frequently attended Quaker meeting with his wife Deborah.

Philadelphia’s Logan Circle

Named for James Logan:

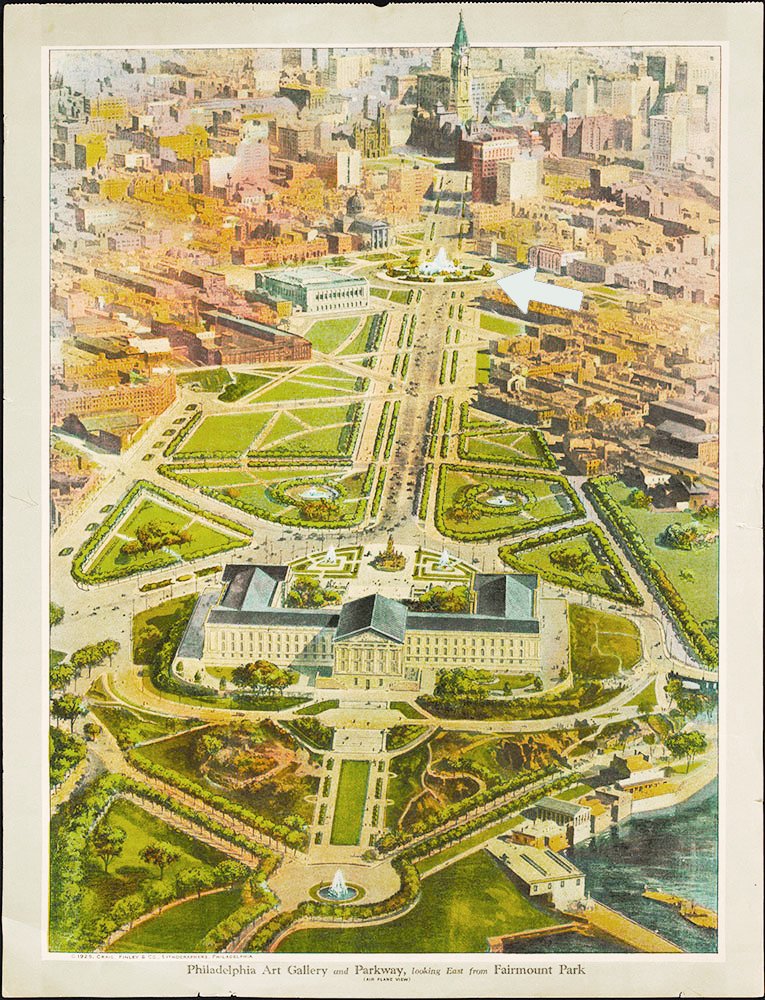

Above: Image source: Free Library of Philadelphia. Craig, Finley & Co., Lithographers, Philadelphia (Digital arrow added)

Above: This 1925 lithography is an artist’s conceptual rendering of the Ben Franklin Parkway. The view leads from the Philadelphia Museum of Art toward City Hall. A fountain in Logan Circle sprays a column of water in front of the Free Library.

Logan Circle is also known as Logan Square. It originally was the Northwest Square in William Penn's plan for the city. In 1825 city officials renamed the square to honor James Logan.

Links: